Recreating History

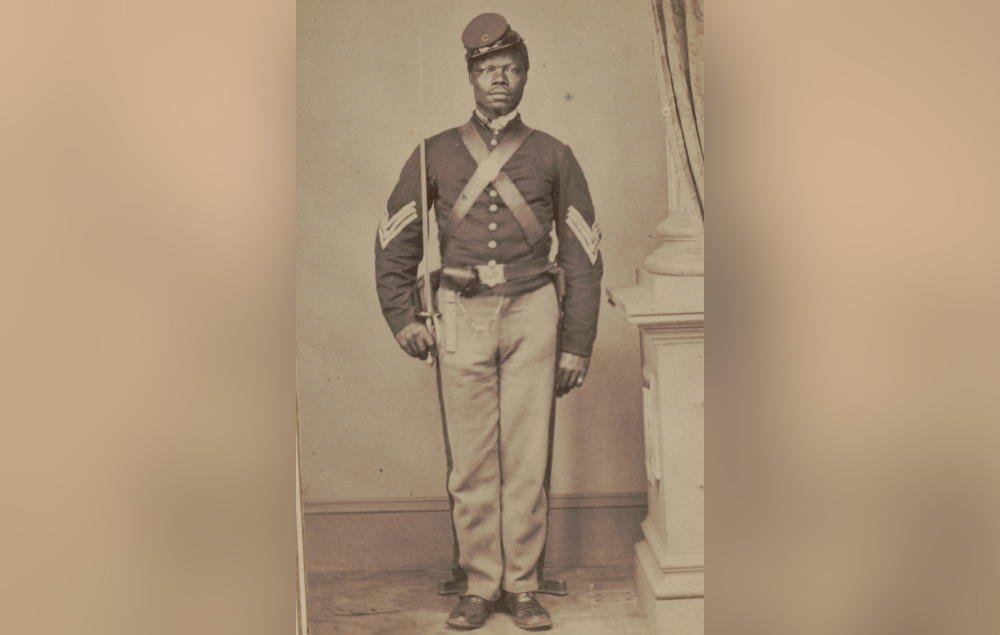

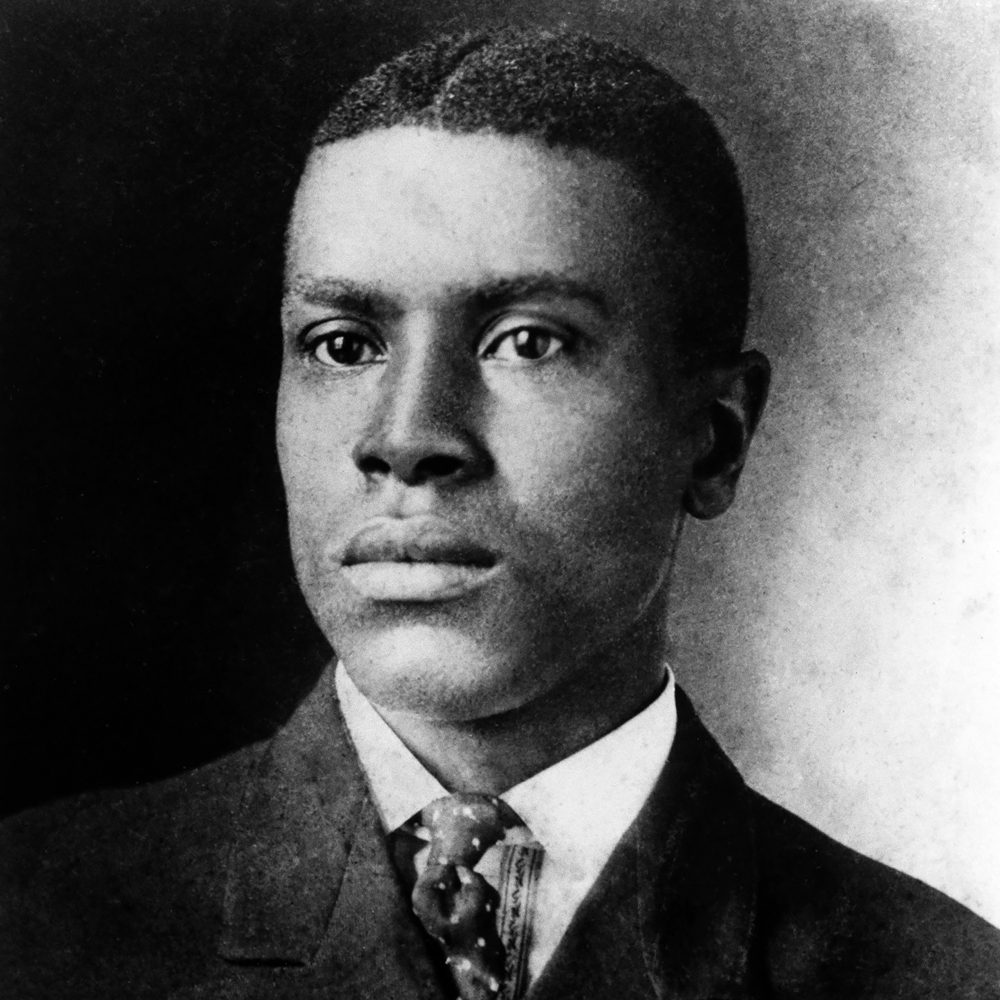

Kwesi Bowman was 21 when he posed for a photo wearing a blue Civil War Union army uniform. Bowman didn’t fight in the Civil War. In fact, he was born in the 21st century. But his great-great grandfather, Andrew Jackson Smith, was a war hero who risked his life to carry his regiment’s battle flag through enemy fire during the Battle of Honey Hill in 1864. Bowman’s photo shoot was part of a project in which descendants of Black Civil War soldiers recreate portraits of their ancestors.

The project is the brainchild of British photographer Drew Gardner. Gardner began taking photos of the descendants of famed historical figures many years ago, but he recently turned his attention to people who changed history but may never have been recognized for it. From there, he decided to try to track down descendants of enslaved people, including Black men who fought in the Civil War.

In 2023, Bowman and many other descendants gathered at a studio in New York City, where Gardner took portraits of them using a 19th-century camera. Each descendant reproduced the pose from their ancestor’s portrait and wore a near-copy of his uniform.

Most of these soldiers are not as well known as Andrew Jackson Smith, whose grandson, Andrew Bowman, Sr. (Kwesi’s grandfather), successfully campaigned to get him a Medal of Honor—the U.S. government’s highest military decoration—in 2001, decades after his death. And it wasn’t easy to link most of the soldiers with their descendants. While Americans whose families immigrated to the United States can often trace their family histories, descendants of enslaved people were included in fewer of the historical documents that researchers often rely on. For example, when enslaved people were listed in records, they were often unnamed. So Garner and a team of researchers had a lot of work to do.

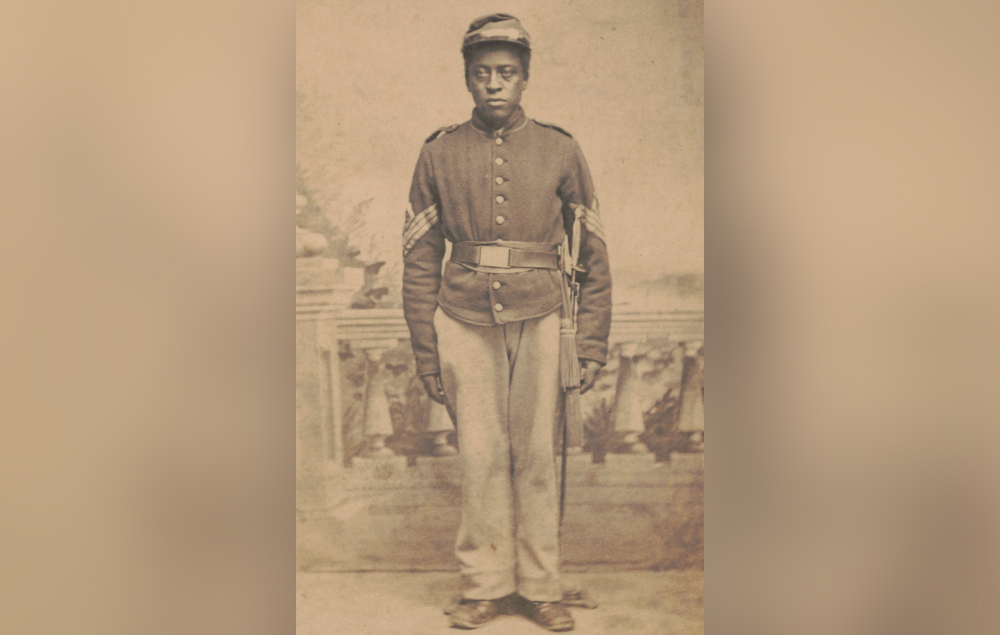

In one case, the team set out to research a Civil War soldier named David Miles Moore, Jr., who was only a teenager when he enlisted in the Union army in 1863. Moore served in the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, the unit of Black soldiers later depicted in the 1989 movie Glory. The researchers unearthed a record showing that Moore had filed for a military pension in 1897 and then found his name in the 1900 U.S. Census. From there, they traced Moore’s family to his living descendants, the Flowers family. It was 9-year-old Neikoye Flowers who recreated a portrait of Moore, holding a drum like the one his ancestor held.

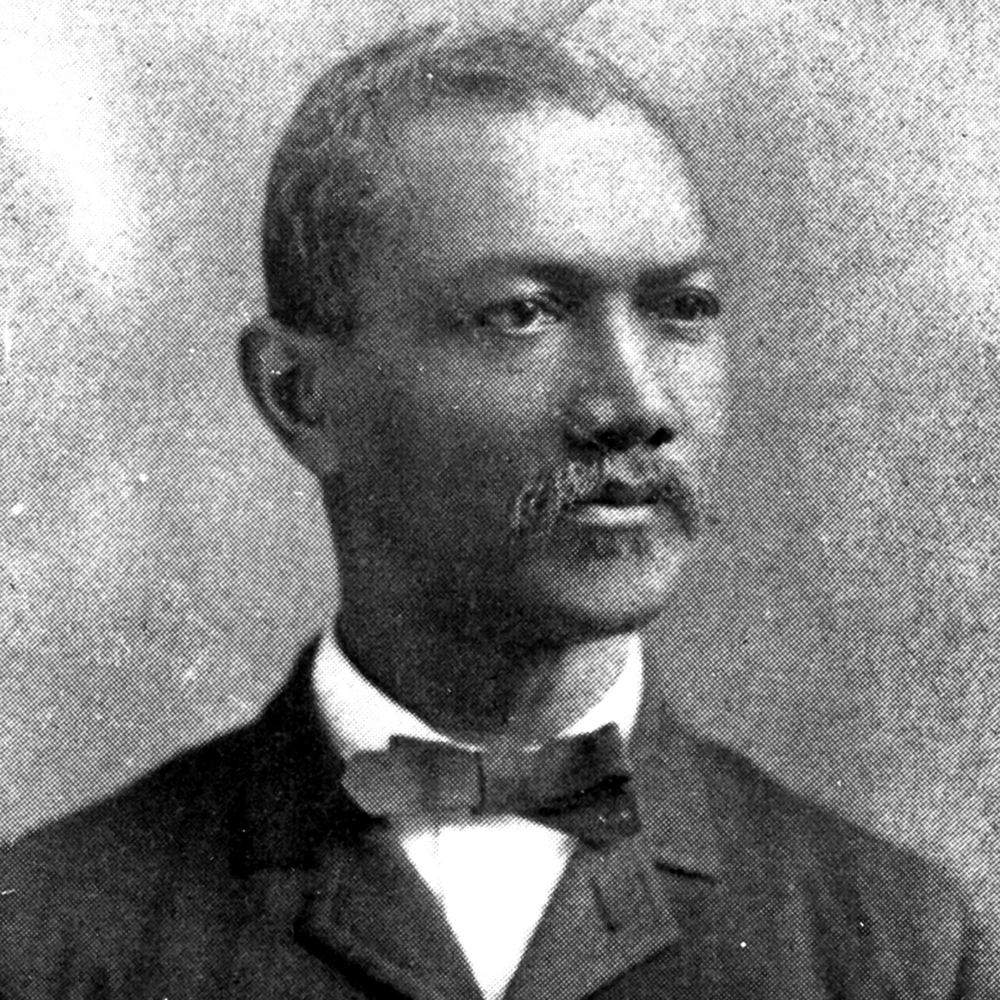

Austin Morris recreated a portrait of his ancestor, Lewis Douglass, a Civil War soldier and the son of famous abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Morris, who is 20, has always known that Frederick Douglass was in his family tree. But dressing up like Lewis made him feel a special connection to the Douglasses.

“I was looking at his picture, thinking: I’m 20. He was in his 20s when the picture was taken. He fought in the war, and he was one of the first Blacks to sign up for it,” Morris told Smithsonian Magazine.

Neikoye Flowers’ mom, Janisse, says this portrait project is giving her son and his twin sister a similar sense of pride.

“They’re going to remember everything about this trip,” Janisse told Smithsonian. “And hopefully it turns that page in history where they can brag about this to their kids and grandkids.”