Kayaking into History

Native American teenagers went on a kayaking journey to celebrate the restoration of a river that has long played an important part in their cultures.

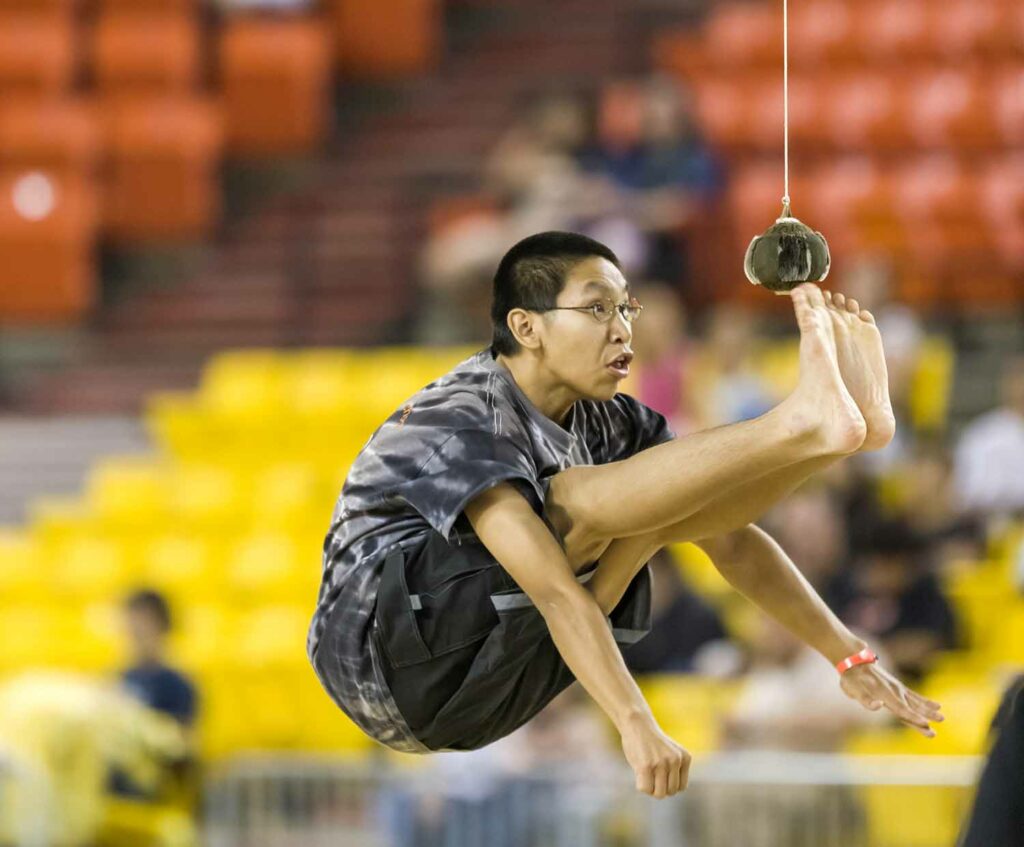

Courtesy of Rios to Rivers

A participant in the Paddle Tribal Waters program kayaks through whitewater in the Klamath River.

This summer, more than 120 Native American teens and young adults completed a historic kayaking trip that hadn’t been possible for more than 100 years. The Indigenous youth paddled 310 miles across 30 days to honor the restoration of the Klamath River, which runs from southern Oregon to northern California in the United States. This event was a celebration honoring the removal of four hydroelectric dams that had previously blocked the river.

Many Indigenous peoples of the U.S. Pacific Northwest region have historically relied on rivers for food, transportation, and cultural connection. For the people of the Klamath River basin, salmon are critical—the Klamath was once the third highest salmon-producing river in the contiguous United States. After 1918, dams blocked the annual salmon migration and thus severed the Indigenous communities’ historic ties to the river.

Since then, these Indigenous communities have been advocating for dam removal and the return of the salmon. Recently, efforts to remove several dams succeeded, and as of 2024 much of the Klamath flows continuously again.

“It’s just a big moment in history, and in everybody’s lives,” Isqotsxoyan Scott, one of the kayakers, told Oregon Public Broadcasting. “All of our families have been fighting for dam removal. Everybody’s been fighting for us to be able to reach different parts of the rivers that we haven’t been able to in over 150 years.”

Kayakers like Scott spent years learning to kayak and navigate whitewater rapids in anticipation of this event. A program called Paddle Tribal Waters taught the Indigenous youth the kayaking skills they would need to be the first to paddle the river from its headwaters to the sea. The Klamath River group included young people from many Indigenous groups, including the Yurok, Klamath, Hoopa Valley, Karuk, Quartz Valley, and Warm Springs—all of which have historic connections to the river valley.

The first generation of salmon to be spawned since the dams were built can now make the return trip up the river.

“The river remembers,” said Susan Masten, a member of the Yurok Tribe. “The fish are coming back to spawn where they haven’t been able to be in a hundred years plus. The fish remember. We, as this river system, are healing.”

Click through the slideshow for more photos from this historic journey!

Courtesy of Erik Boomer/Rios to Rivers, Courtesy of Erik Boomer/Rios to Rivers, Courtesy of Erik Boomer/Rios to Rivers, Courtesy of Rios to Rivers, Courtesy of Matt Baker/Rios to Rivers, Courtesy of Erik Boomer/Rios to Rivers, Courtesy of Erik Boomer/Rios to Rivers