Keeping Traditions Alive

Keiki hula, or children’s hula, helps preserve an important part of Hawaiian culture.

© Scott Cunningham/Getty Images

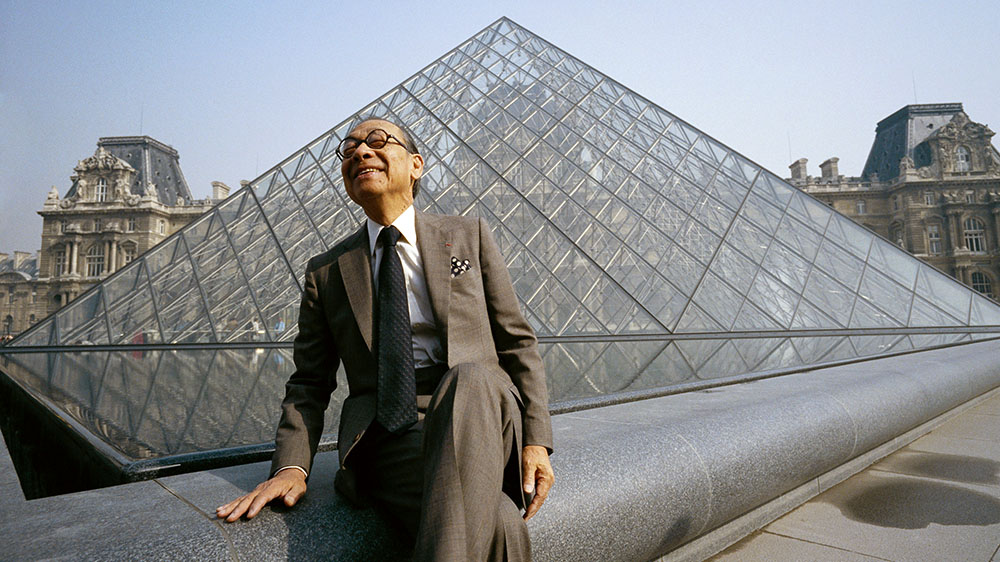

Hula dancing is an important part of Hawaiian culture. In this photo, hula dancers perform at the 2013 Pro Bowl in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Before people had written language, historic events and stories still needed to be passed down to young people. But how? Some cultures used storytelling and poetry to record and share history. The native people of Hawaii (called Hawaiʻi in their language) used hula dancing. Today, young hula dancers help keep the tradition alive.

Dancers aged 6 to 12 perform keiki hula, which means “children’s hula” in Hawaiian. Each July, hundreds of children from across the Hawaiian Islands come together for the Queen Lili‘uokalani Keiki Hula Competition. This three-day event is named in honor of the last monarch to rule Hawaii before the islands became part of the United States. (A monarch is a king or queen.)

The competition celebrates the passing of tradition from one generation to the next. Native Hawaiians did not have a written language until the 1820s. For centuries, they used hula to tell mythical and historical stories about people, places, and gods and goddesses. Keiki hula ensures children will help preserve this important part of their culture.

© Scott Cunningham/Getty Images

Hula dancers perform at the 2014 Pro Bowl in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Hula is recognizable for its graceful arm and foot movements and hip sways. Dancers learn the dance steps and songs from a kumu hula, or dance instructor, in hula schools called hālau. The music and dance moves of hula have specific meanings that help with the storytelling of the dance. The performers may wear traditional leaf skirts called paʻu or a type of loincloth called a malo. They adorn their heads, wrists, and ankles with leaves, flowers, feathers, or shells.

Despite hula’s importance, there was a period in the mid-1800s when it was discouraged. In 1820, Christian missionaries from the United States converted many native Hawaiians to their religion, including members of the Hawaiian monarchy, who then banned public hula performances. As a result, the dance could be taught only in secret until the 1880s, when King David Kalākaua encouraged hula’s return.

Today, traditional and modern hula dancing is celebrated. This year, the Queen Lili‘uokalani Keiki Hula Competition is celebrating its 50th anniversary, marking half a century of keeping the hula tradition alive by teaching it to children.