A Field of American Dreams

During World War II, Japanese American citizens were imprisoned by their own country. A field where they played baseball is a symbol of strength and resilience.

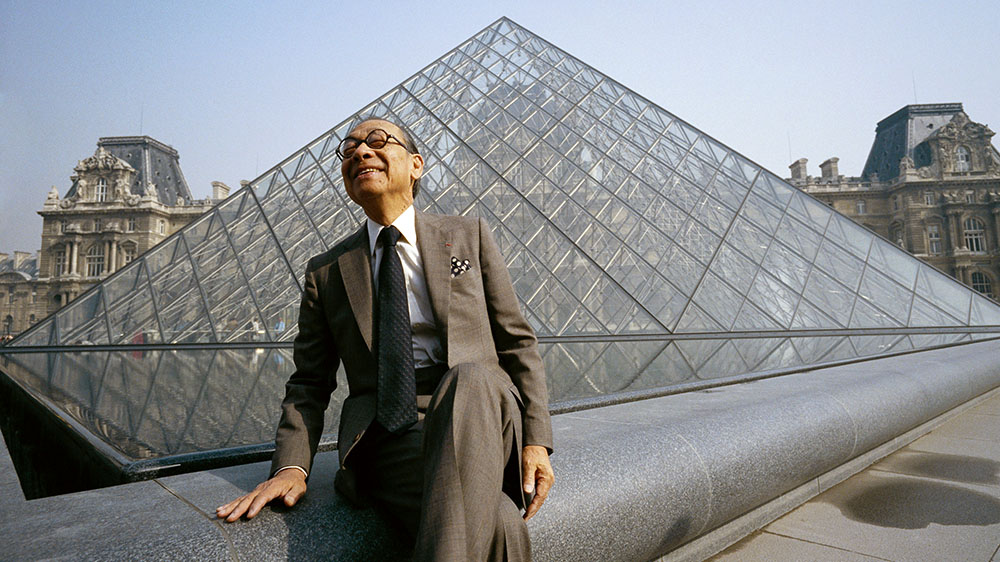

© Brian van der Brug—Los Angeles Times/Getty Images

Dan Kwong (number 12) and Logan Morita (number 3) during a game that reopened the restored baseball diamond at Manzanar National Historic Site.

A baseball field with a painful past is getting a historic revival. In October 2024, baseball players from across the West Coast of the United States gathered to play on the restored field at Manzanar, California, where thousands of Japanese American citizens were once imprisoned. Despite the baseball field’s dark history, many people consider it to be a symbol of strength and resilience.

During World War II, the U.S. government forced 120,000 Japanese Americans to relocate to prison camps. The government justified this by claiming that Americans of Japanese descent might be reporting U.S. secrets to Japan, which was then an enemy nation. Despite their loyalty to the U.S., these Americans swiftly lost their rights. Whole families were forced to move into camps. These prison camps became known as Japanese American internment camps.

One of these camps was at Manzanar. The camp was located near Death Valley, a desolate place where temperatures range from severely hot to very cold. People lived in barracks behind barbed wire fences. Guards watched them and would not let them leave.

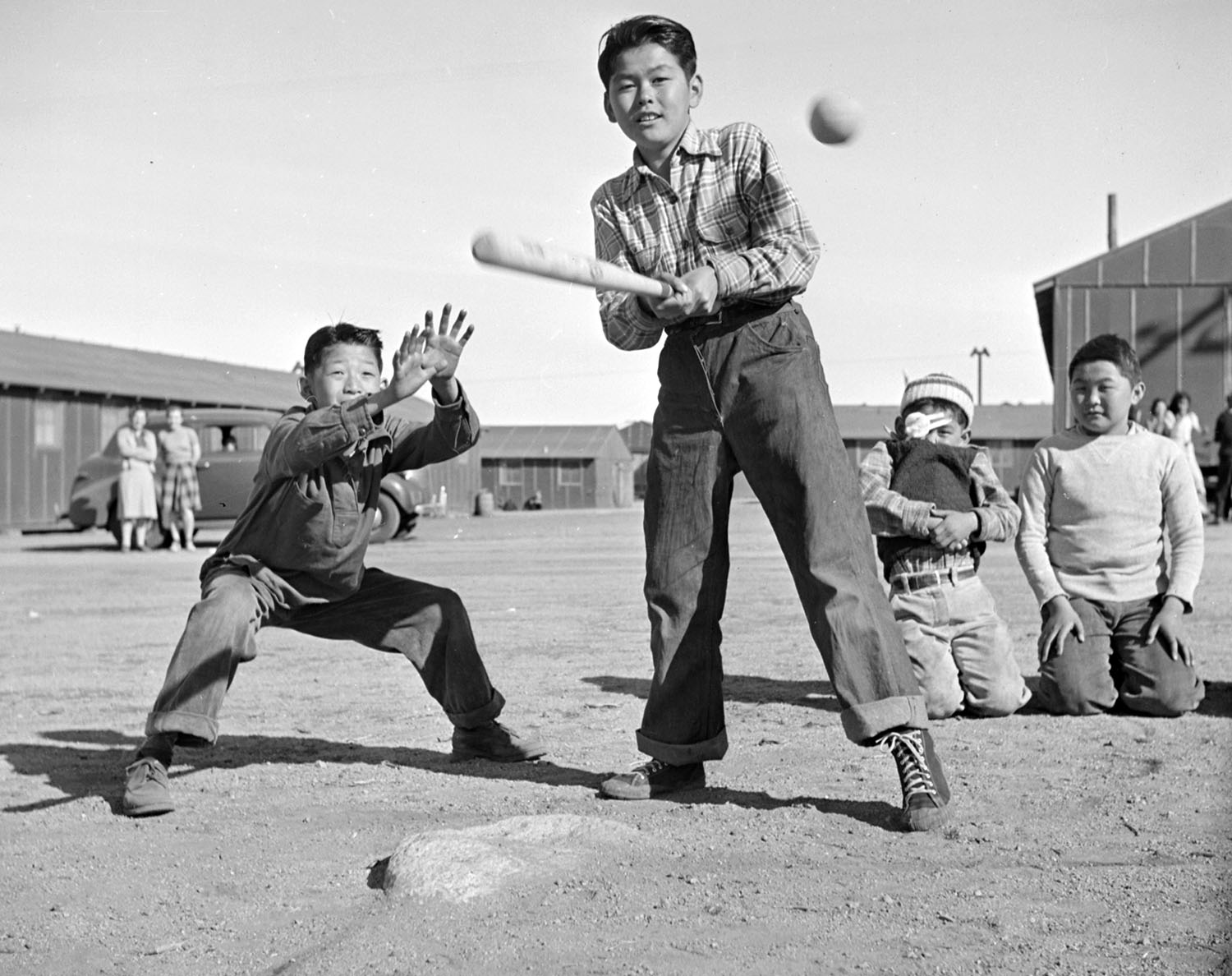

National Archives, Washington, D.C

In this 1943 photo, 6th graders play a game of softball at recess from school at the Manzanar War Relocation Center.

However, the Americans imprisoned at Manzanar were resilient. They began to do things to make life at the camp a little more tolerable.

“Baseball played a few different functions in camp,” Dan Kwong told Smithsonian magazine. “One, it was a piece of their normal life that they were allowed to keep. Two, it gave them something to do in the face of crushing boredom. And then three, perhaps most profoundly, it was symbolic of being American.” Kwong is a baseball player in a Japanese American league. His mother was imprisoned at Manzanar with her family when she was a young woman.

Despite being mistreated by their government, the Americans at Manzanar remained devoted to their country. Baseball was an outlet that connected them to their community while also passing the time and making them feel a bit more normal amid war.

“There were people who said, ‘…We know we’re Americans. Our country has rejected us, but we are not rejecting our country,’” said Kwong, who helped lead the restoration of the Manzanar field.

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; Ansel Adams

People gather outside a church at the Manzanar War Relocation Center during World War II.

The war ended in 1945, and the government let the prisoners return to their lives. The internment camps were torn down. In 1992, Manzanar was designated as a historical site, and restoration began. But it wasn’t until 2023 that they began restoring the baseball field.

The October 2024 game took place after a year of restoration work. Four Japanese American baseball league teams played a ceremonial doubleheader—two games in one day—to celebrate the restoration. The first game was between amateur teams called the Little Tokyo Giants and the Lodi Templars, which are the longest continuously active teams in California. The second game was the North versus South All-Star Game, in which the players wore vintage-style baseball uniforms. Several of the players were descendants of those imprisoned in Manzanar or other internment camps. Another doubleheader is planned for later this year.

“The…purpose of this baseball field and baseball game is for the Japanese American community itself,” said Kwong. “It represents a will to thrive and flourish no matter what conditions you are put under.”

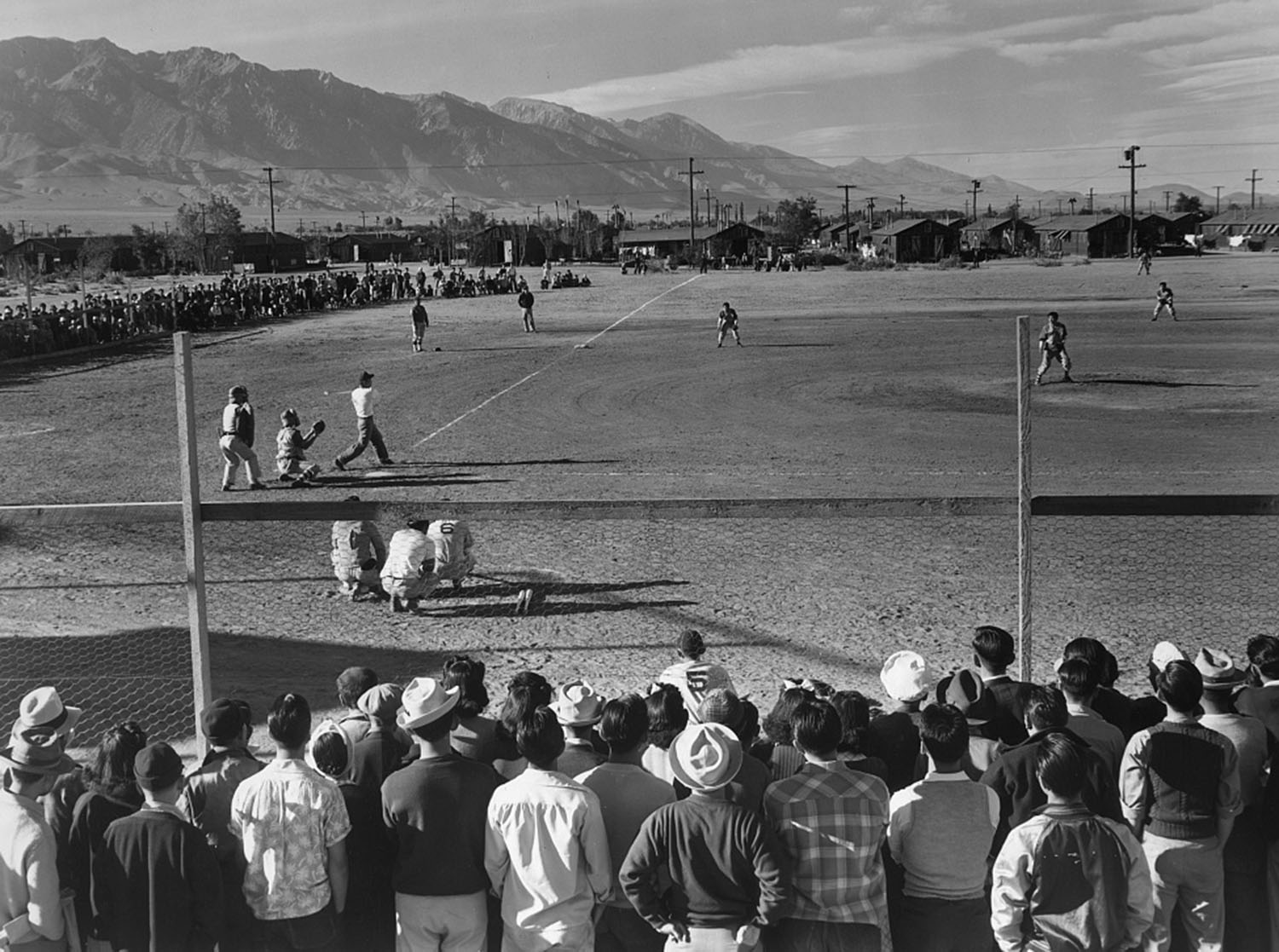

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; Ansel Adams

A baseball game is played at the Manzanar War Relocation Center in 1943.