Harnessing a Wild River

The Hoover Dam made the Southwestern United States a lot more livable, but is our planet paying the price? Author Simon Boughton shares his thoughts.

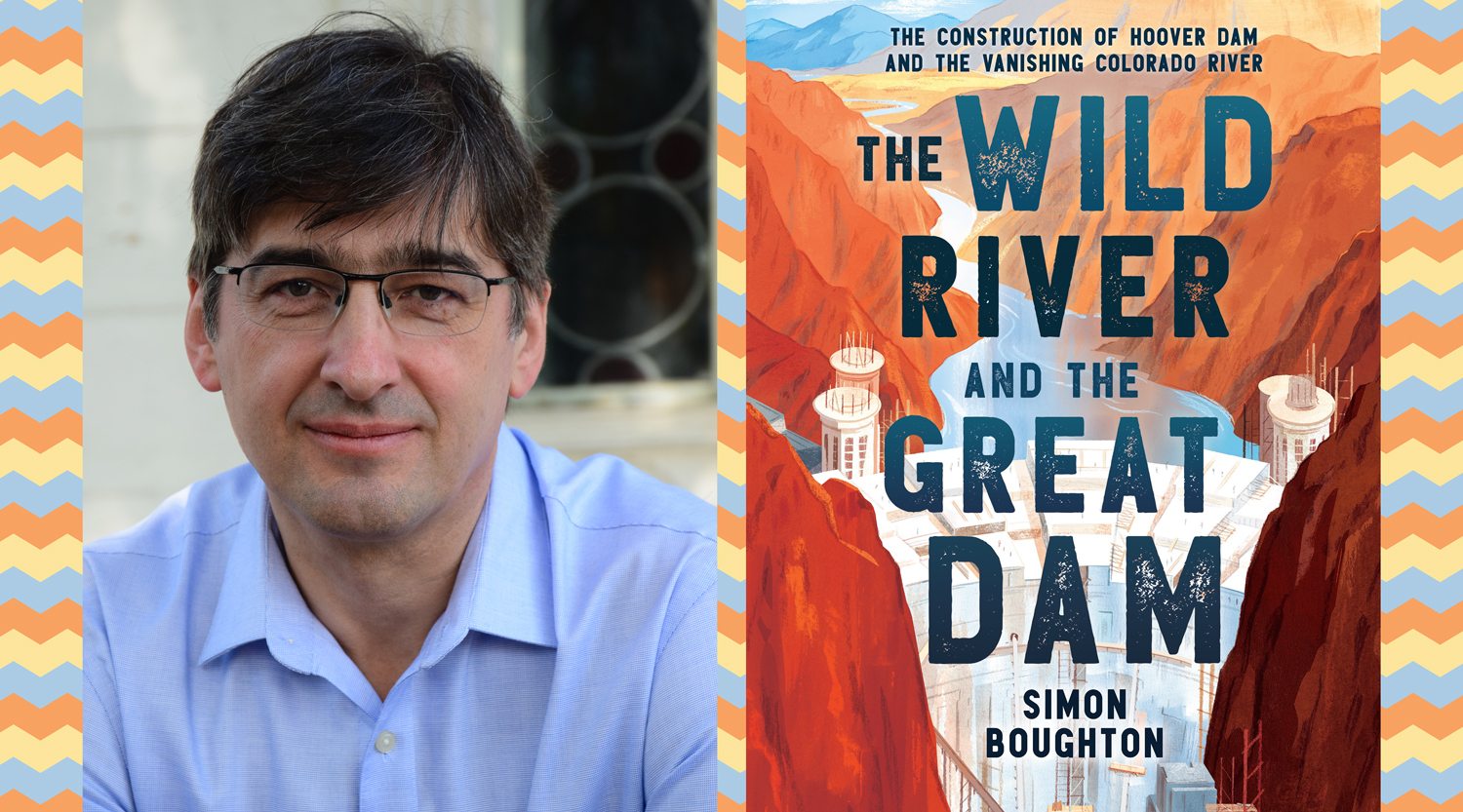

Simon Boughton’s new book, The Wild River and the Great Dam, tells the story of the Hoover Dam with photos and firsthand accounts.

The Colorado River is amazing. Flowing from the state of Colorado down to Mexico, the river provides water and electric power to people throughout the arid Southwest. This wouldn’t be possible without a feat of human engineering called the Hoover Dam. Built in the 1930s by the U.S. government, the dam harnessed the power of the unpredictable river, turning it into a valuable resource. But the Hoover Dam has also had negative environmental consequences.

In a new book called The Wild River and the Great Dam, author Simon Boughton explores the construction of the dam and its impact on the natural world. The book is filled with historical photos and quotes from people who were involved in the Hoover Dam project. To mark Earth Day (April 22), In the News spoke to Boughton about how the dam has affected our planet. Here is a condensed and edited version of our conversation.

In the News: Why did you choose the Hoover Dam as your topic?

Simon Boughton: I had a childhood fascination with big things and big machines and building things. This book began with that childhood fascination with construction. I was interested in the audacious engineering story, just building this huge thing in the desert with new machinery. And it does turn out to be an engineering story about solving problems and building big things. The other thing that really spoke to me about it is that it turned out to be a really interesting human story as well as a piece of social history. I found it really fascinating.

ITN: In the book, you point out that the Southwest is largely desert. Why did people want to change that by building a dam that would supply water?

SB: It’s not an easy thing to settle in a desert. So, it was just a matter of practical necessity to support this flood of people that came from the East to the West during the late 19th century and early 20th century. In order for more people to live there, there has to be water.

ITK: This land had to be turned into something that was usable.

SB: Yeah, I mean, I’m very conscious when thinking about the story that I don’t think it was inevitable that this had to happen. It’s a story about something that, to some people, seemed like a good idea but turned out to have other consequences. I’m wary of sounding like it was something we had to do. It’s something we chose to do.

ITK: It felt like from the government’s perspective that they believed that they had to do it. But that’s just one perspective. In your book, you quoted U.S. Secretary of the Interior Ray Lyman Wilbur. In 1930, he said the Hoover Dam would be “one of man’s greatest victories over nature.”

SB: Yeah, that’s particularly the language [of that era] of sort of bringing nature into subjugation. There’s also a quote about the river running wild through the West and resembling an untamed horse, and finally [after the dam was built], the horse being tamed and harnessed.

There are [also] these different ways that the word conservation came to be understood over the course of the 20th century. [At one time], if water reached the sea without being used, it was considered wasted, so that their version of conservation was that you had to put water to use. Today, we talk about conservation as something else—not using too much of a resource or being careful how we use it.

ITK: Can you talk a little bit about the positive and negative impacts of the dam?

SB: The dam was a success in the short term. The amount of water that was stored by the dam and the amount of power that was generated by the dam was far in excess of what people thought they needed at the time. The impact of the building of the dam on the farming communities down river was almost immediate. Immediately, the supply of water became predictable and reliable and manageable. But because it was a success, it created a kind of hunger for more. I think what happened was that the government got caught up in this cycle of trying to squeeze more out of the river over the second part of the 20th century. The story became one of trying to get ahead of economic and population growth.

ITK: And then the government started building more dams.

SB: Yes, I think one consequence of the success of Hoover Dam was this rush to build on its success without really thinking through what the consequences might be. And then I think the other one is that they created a dependency on the Colorado River.

IKN: You write in the book about how climate change has really made that problem worse because rainfall is less predictable. I’m sure that, back when the Hoover Dam was built, they weren’t thinking about climate change.

SB: Sure.

IKN: What can be done to deal with the effects of climate change?

SB: The dam was built because people wanted a solution to a resource problem, which was dry land with unpredictable cycles of droughts and floods. Cities and communities were growing, and they needed a solution. So really, the ingenuity and the creativity and the sense of purpose that built the Hoover Dam could be applied to the current situation. We are an ingenious species. You can think about building infrastructure that preserves water or uses it wisely, whether it’s through recycling water or using less water.

In the longer term, we ought to think about what we grow and when we grow it. So, for example, about 80 percent of the water that is taken out of the Colorado River goes to support agriculture. Farming is clearly something that is necessary for a growing population. On the other hand, a lot of that water goes to support things like cattle, for example, or avocados in winter. Do we need to have fresh vegetables in winter? Are there alternatives that are sustainable in terms of where we grow our food, how we grow it, and how we get it to where it’s needed? Those are really, really big questions.