Cracking the Code

When antique collector Sara Rivers Cofield found strings of unrelated words written on two pieces of paper from the 1880s, she had no idea what they meant—and neither did many code experts. Now, the mystery has been solved. It turns out that Rivers Cofield’s mysterious messages were probably old-fashioned weather reports.

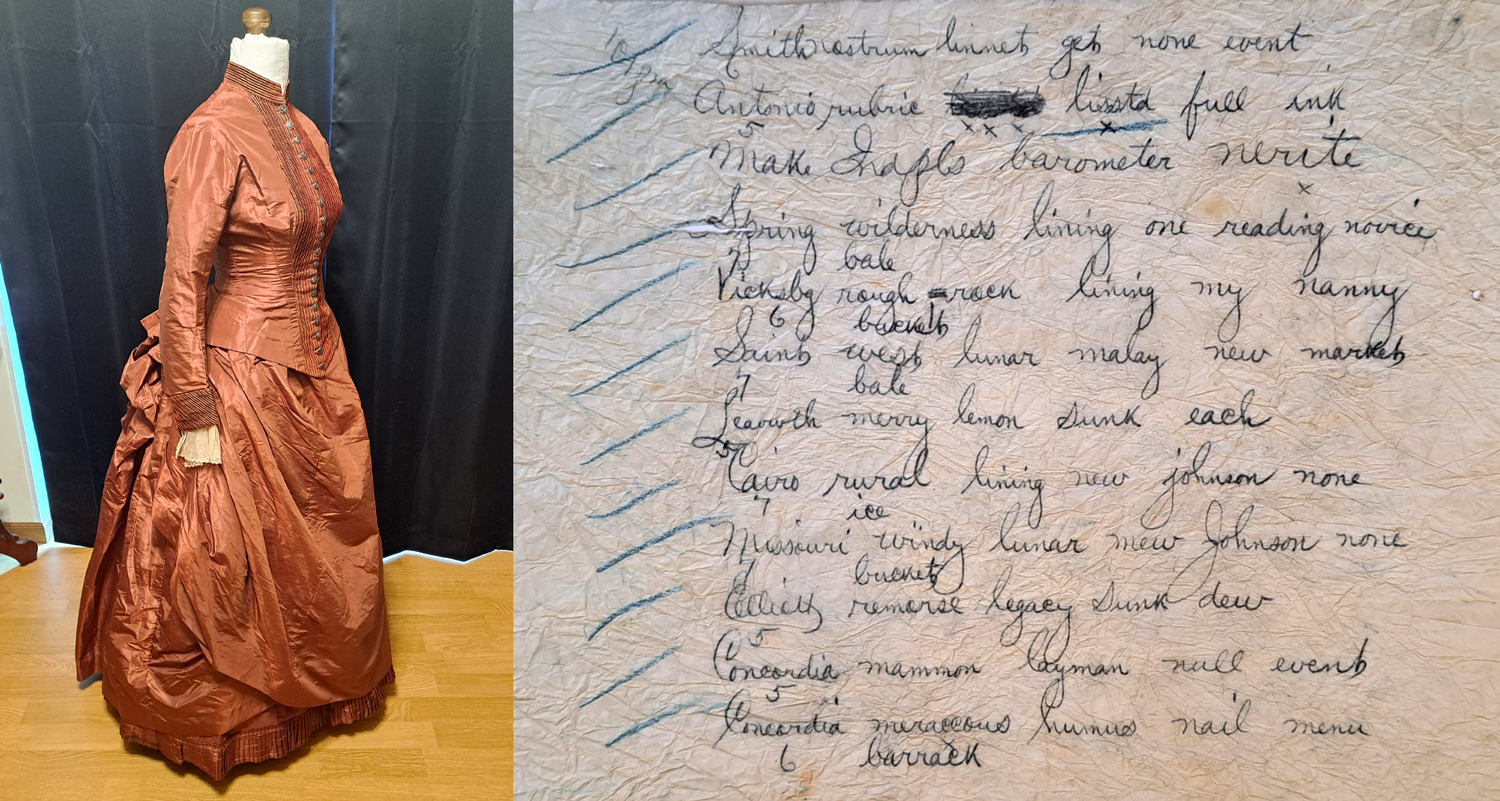

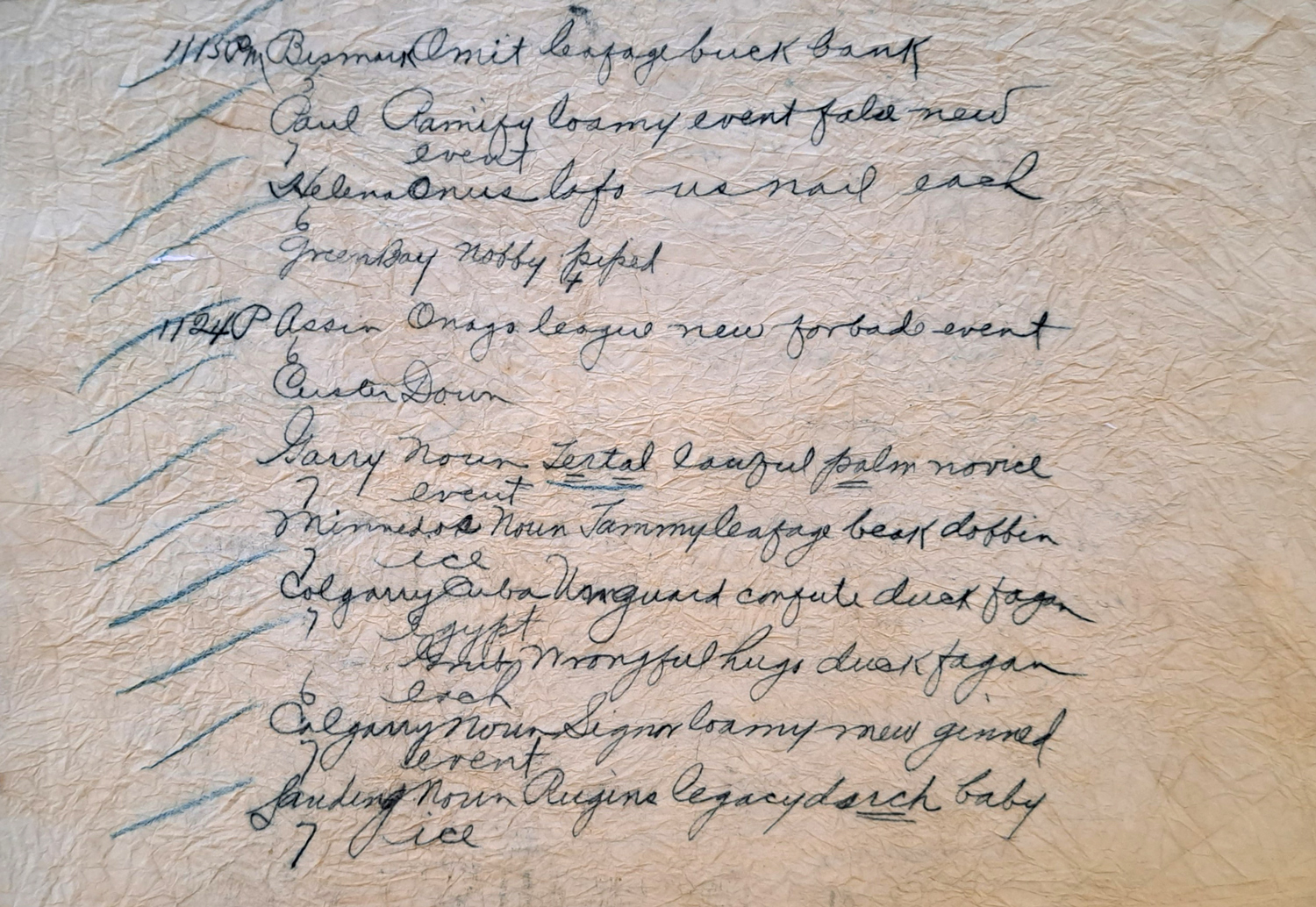

Rivers Cofield found the messages in a hidden pocket of an antique dress she’d purchased in 2013. The handwritten words didn’t make much sense together. In fact, they didn’t seem related at all. One line read, “Bismark omit leafage buck bank,” and there were many more like it. Perplexed, Rivers Cofield went online and asked for help. Clearly, this was some kind of code—but what code was it, and how could it be cracked?

The line “Bismark omit leafage buck bank,” can be seen in this piece of paper. What does it mean?

Many people who studied the messages said they believed the code was designed for transmitting telegraphic messages. Invented in the 1830s, the telegraph was a device that could be used to quickly send messages (called telegrams) over distances long before email, texting, or even the telephone existed. The instant messaging of its day, the telegraph offered a much faster form of communication than letter writing. People who sent telegrams had to pay by the word, so it was preferable to make messages as short as possible. Telegraphic codes allowed senders to communicate a full sentence using just one or two words.

But if the messages in the antique dress were written in telegraphic code, which telegraphic code was it? Hundreds of codes were developed by the military, the railroads, and many other companies.

In 2022, research computer analyst Wayne Chan figured it out. After seeing the handwritten words transcribed online, Chan looked through about 170 code books, searching for matches. He found nothing at first. Then, in a book about the history of the telegraph, Chan read about weather codes. These codes were game changers in their day. For the first time, people received information about storms and other weather events via telegram instead of being taken by surprise.

With help from a librarian at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Chan obtained a copy of a late 19th century weather code book used by the U.S. Army Signal Corps and realized that the messages found in the dress were weather reports. Hidden in those “nonsense” words, there was information about temperature, barometric pressure, precipitation, and more.

Who wore the dress and carried those weather reports? No one knows for sure, but Chan and Rivers Cofield speculate that it might have been an employee at the U.S. Army Signal Service in Washington, D.C.

That part of the case will probably remain unsolved.