The Road to Equal Rights

July 19 is the anniversary of the first day of the Seneca Falls Convention, a two-day meeting where attendees spoke out for women’s rights.

© Kean Collection—Archive Photos/Getty Images, © Hulton Archive—Archive Photos/Getty Images, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., © atdr/stock.adobe.com; Photo illustration Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

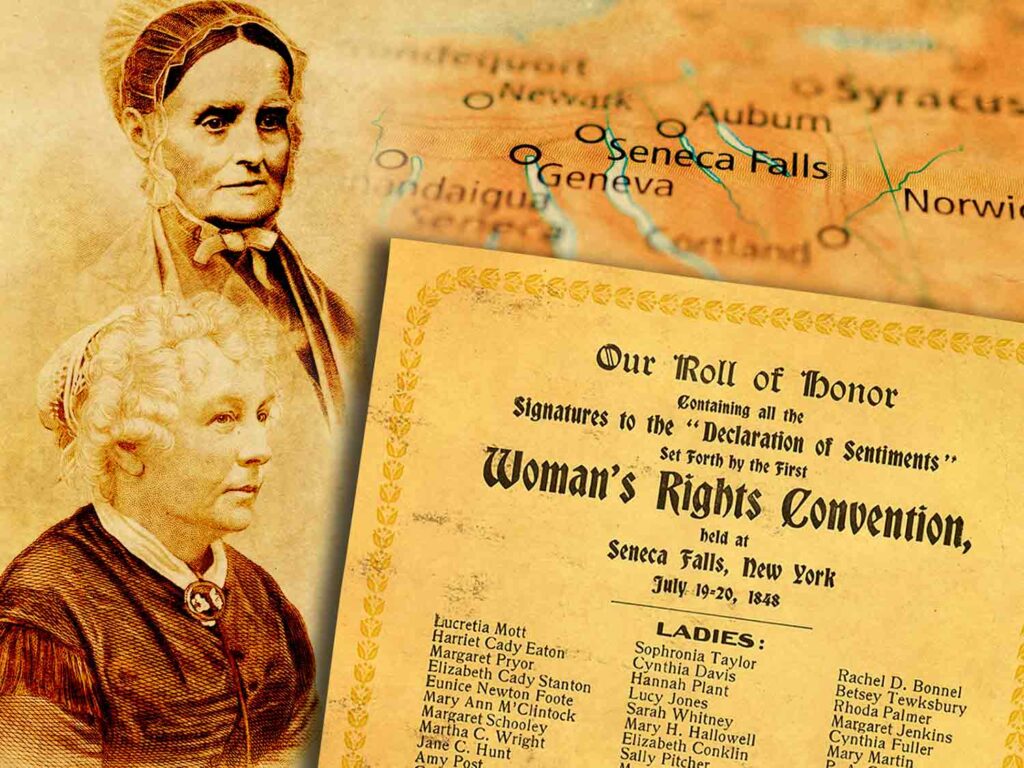

Lucretia Mott (top) and Elizabeth Cady Stanton organized the Seneca Falls Convention.

July 19 is the anniversary of the first day of the Seneca Falls Convention, which took place in 1848 in Seneca Falls, New York. The event, organized by activists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, aimed to expand women’s rights in the United States.

Although the United States was founded under the ideal that “all men are created equal,” Stanton, Mott, and other activists knew this wasn’t the reality. Only white men had guaranteed rights. Other Americans did not. This was especially true for enslaved Black Americans. The law did not even consider enslaved people to be people. White women were far better off, but they didn’t have the same rights as white men. In most states, they weren’t allowed to sign contracts or own property, and their educational opportunities were limited. And since women weren’t allowed to vote, they were unable to participate in elections for leaders who would champion their cause. The purpose of the Seneca Falls Convention was to draw attention to these inequalities and challenge the nation to live up to its ideals.

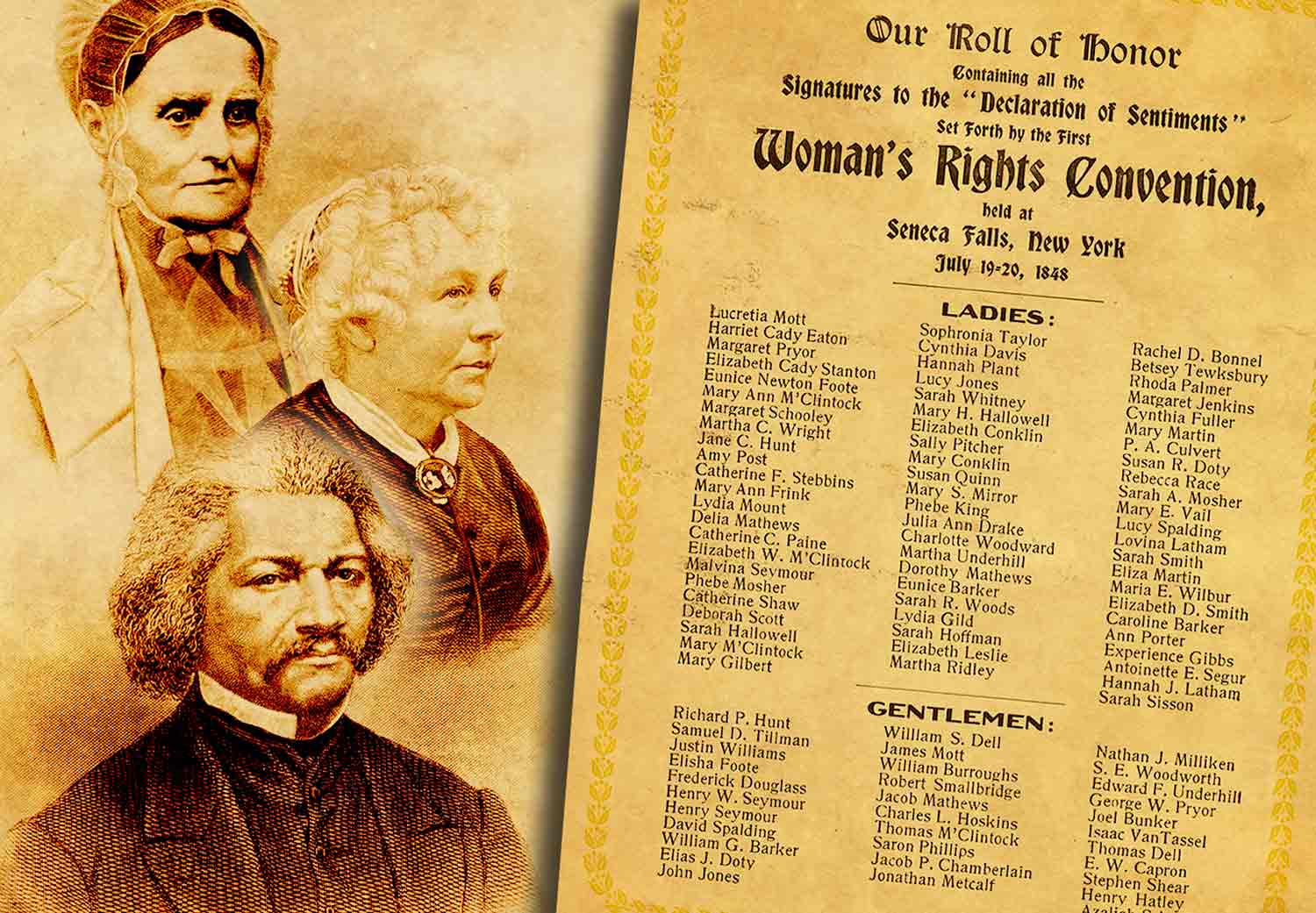

The two-day event drew more than 300 women and men. The attendees discussed whether to adopt a document called the Declaration of Sentiments. Written by Stanton and modeled after the Declaration of Independence, the document began, “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal.” It resolved that, under the ideals of the United States, women were entitled to certain rights, including property ownership, equal education, and suffrage (the right to vote).

Only one of the resolutions in the Declaration of Sentiments turned out to be controversial—women’s suffrage. But Stanton, along with abolitionist Frederick Douglass, were eventually able to convince enough attendees to support voting rights for women. The document was ratified on July 20.

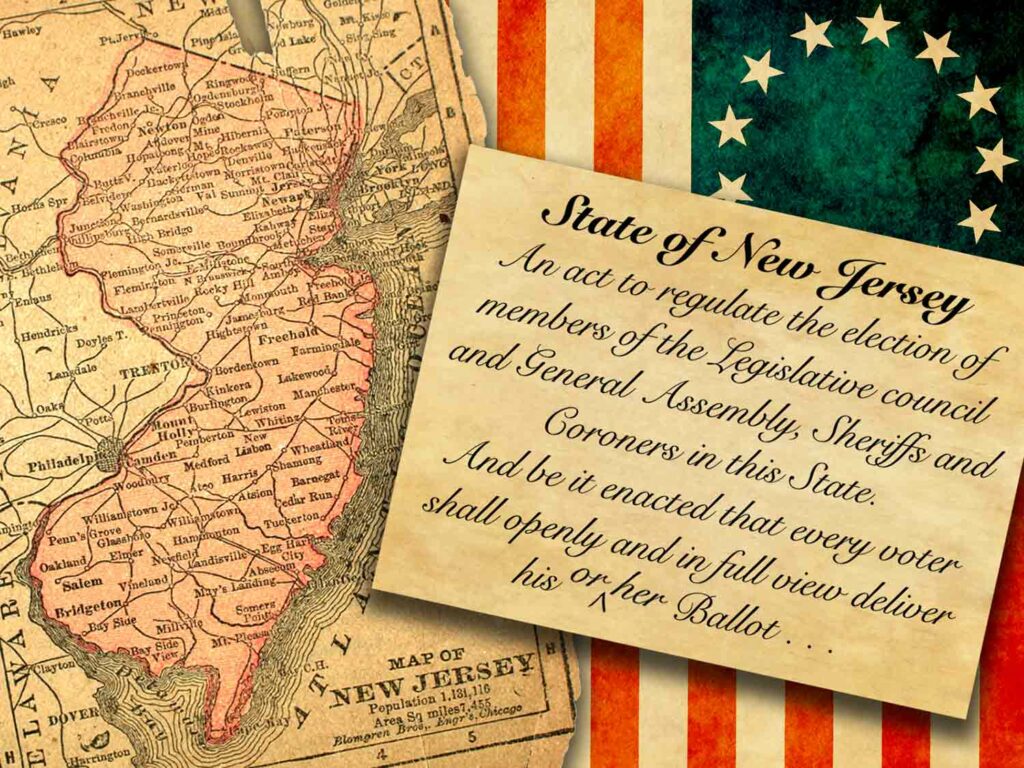

Seneca Falls was only one milestone in a long fight for women’s rights. In the decades that followed, many states would pass laws that expanded certain rights for women. In 1869, Wyoming (which wasn’t yet a state) granted women full voting rights. Some other states and territories followed. More than 50 years later, in 1920, Congress ratified the 19th Amendment, which guaranteed women in the United States the right to vote.

You can read the Declaration of Sentiments at Britannica School.