Recreating an Ancient Voyage

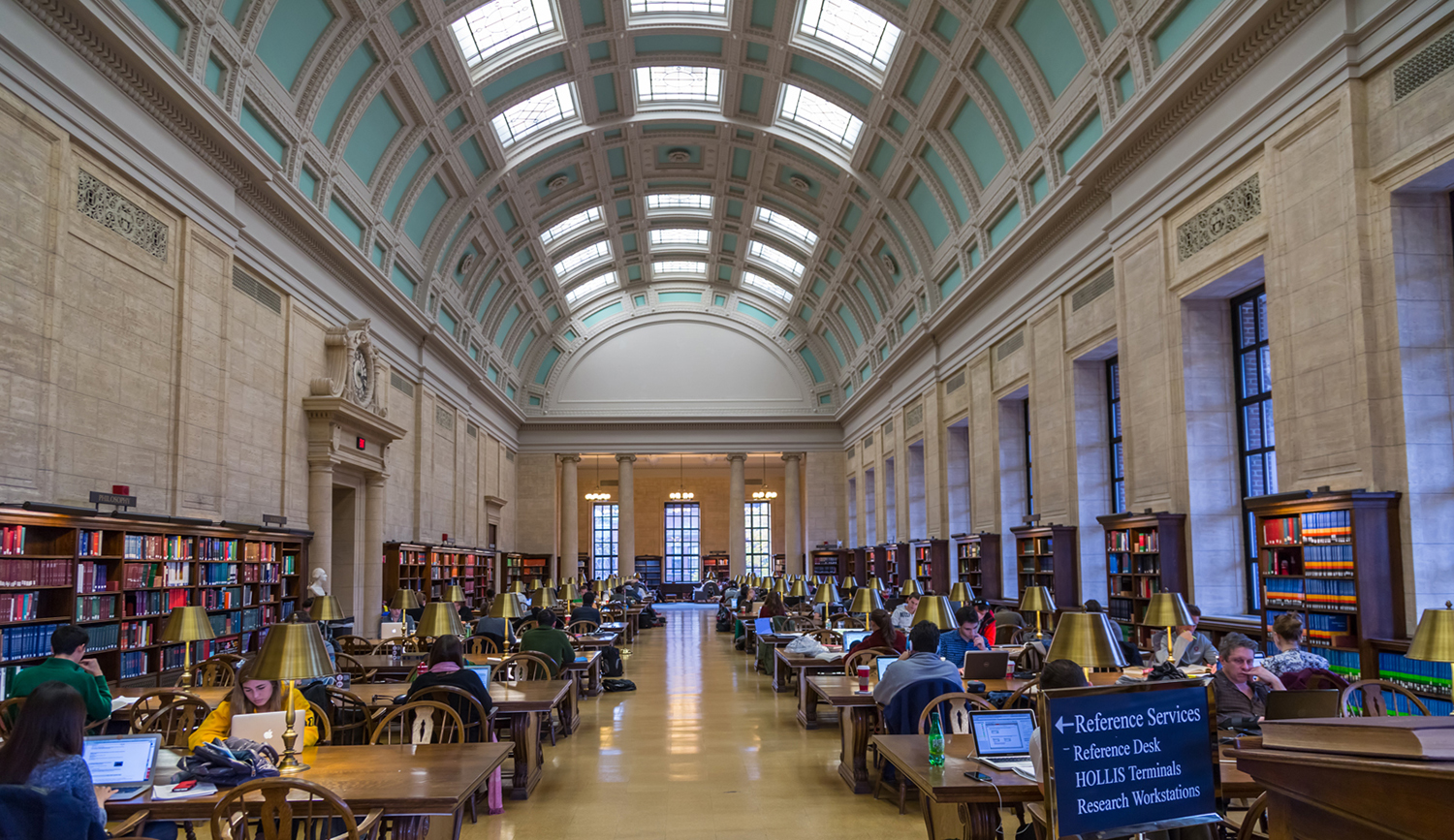

Scientists recreated a sea voyage to see how ancient people made their way from Taiwan to a Japanese island.

Courtesy of © Yousuke Kaifu/The University Museum, The University of Tokyo

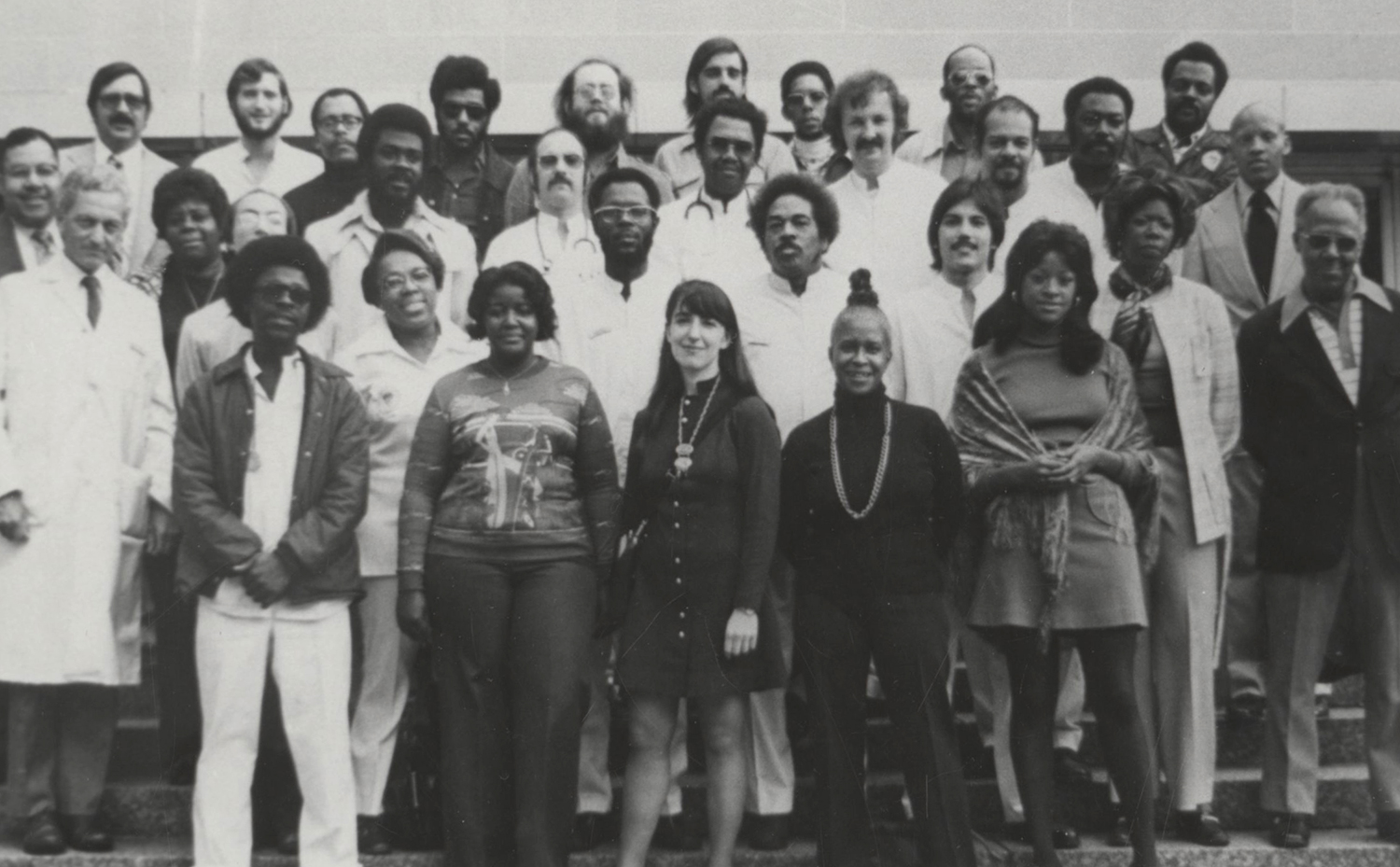

A team of scientists from the University of Tokyo paddle from Taiwan to Japan’s Yonaguni Island in a canoe they built.

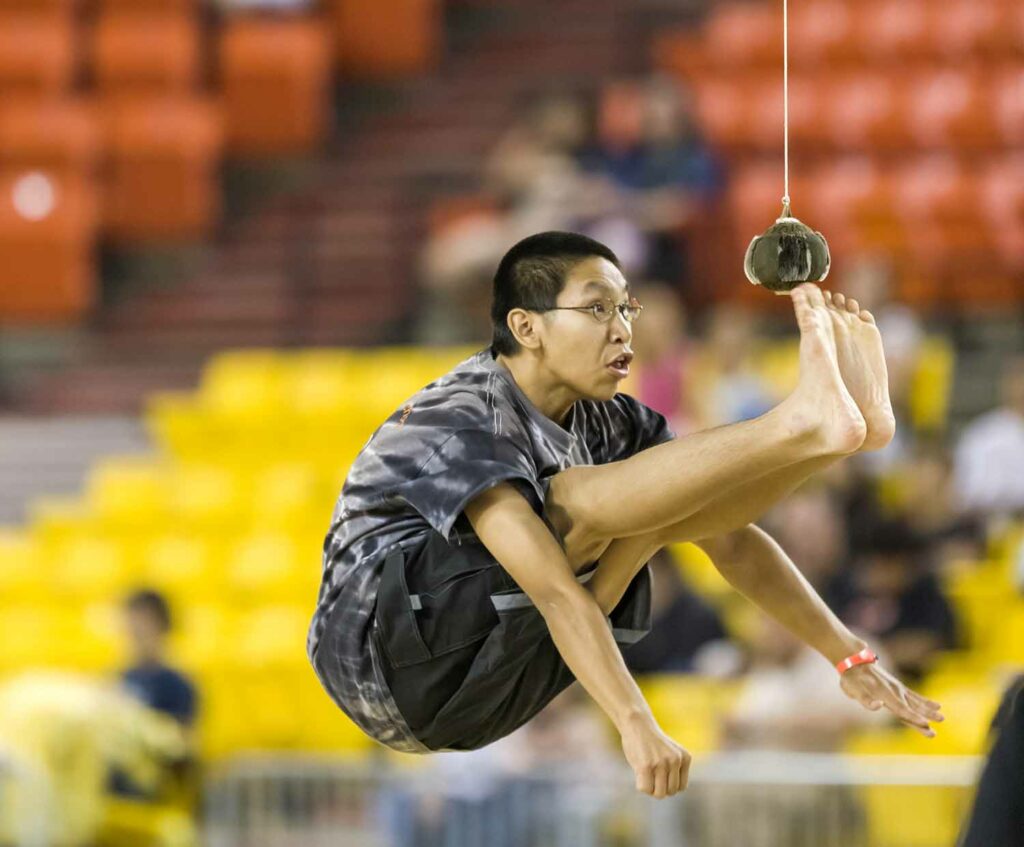

Imagine going on a long sea voyage with no modern navigational tools. About 30,000 years ago, a group of people traveled on rough seas from Taiwan to an island in Japan with no instruments, landmarks, or maps to guide them. To find out how they did it, scientists decided to re-create the journey.

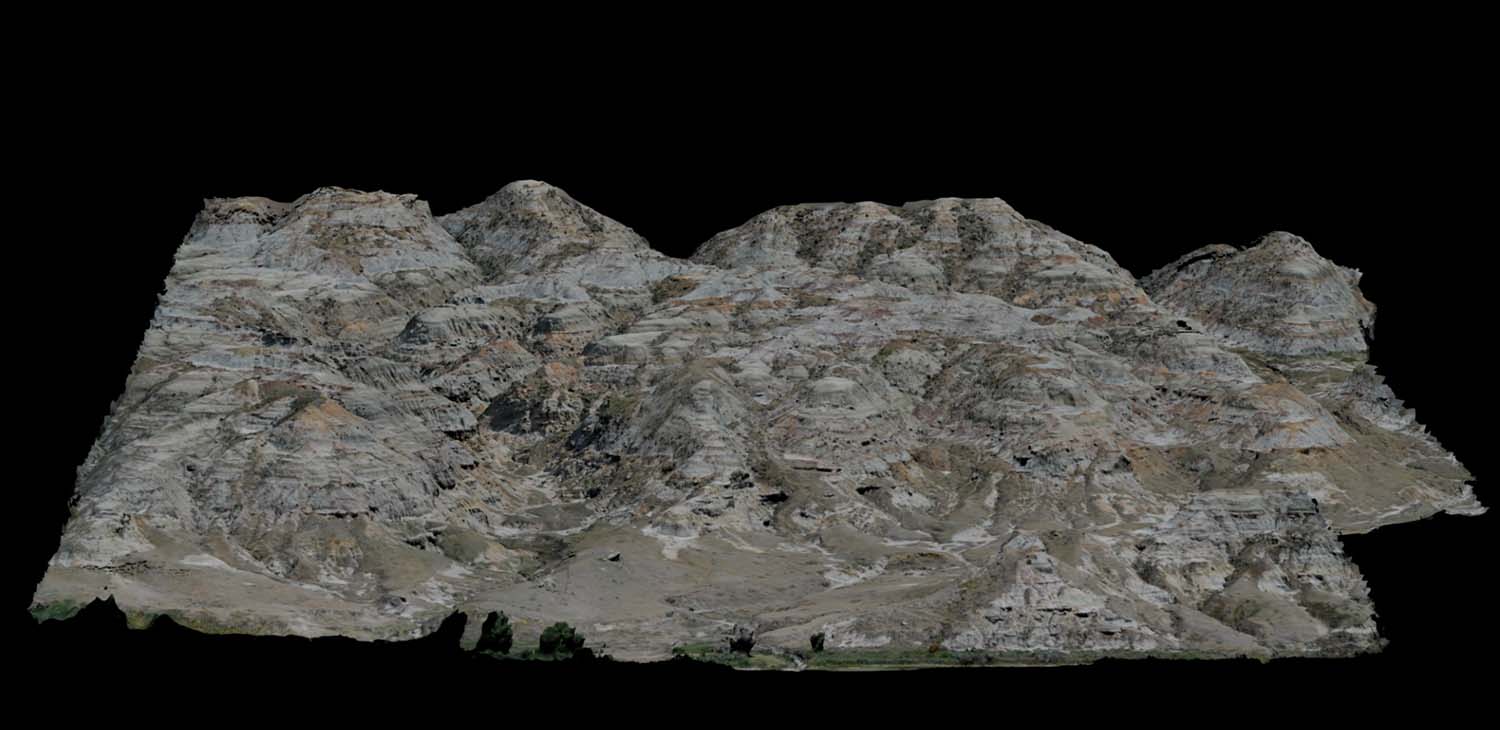

When a team of researchers from Japan and Taiwan set out to determine how ancient people traveled 140 miles (225 kilometers) from Taiwan to the southern Japanese island of Yonaguni, they knew two things: First, the settlers must have traveled by sea, as there was no other way to reach an island. Second, they would have had to battle the area’s powerful Kuroshio current, which is notoriously difficult.

Courtesy of © Yousuke Kaifu/The University Museum, The University of Tokyo

Scientists recreated an ancient stone axe with a wood handle to chop down a Japanese cedar tree that they used to build a canoe.

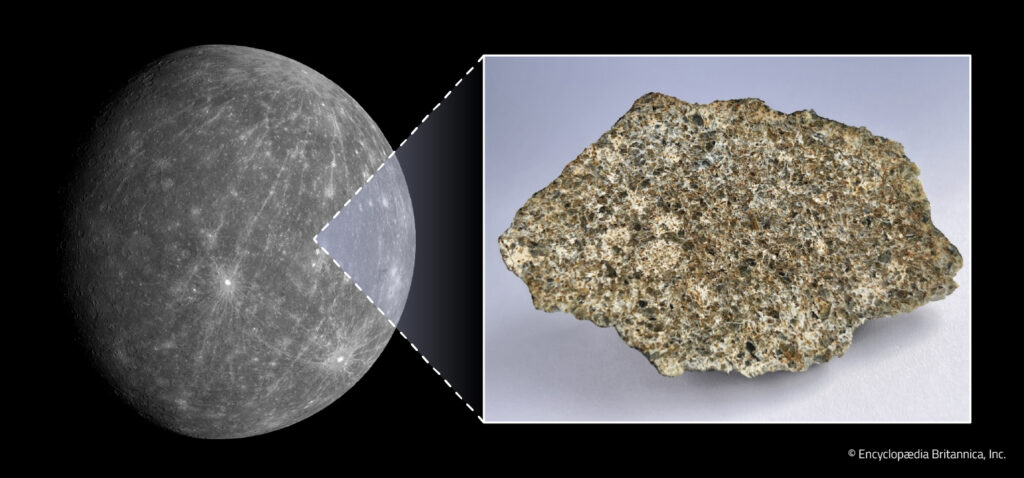

The researchers knew that rafts wouldn’t be strong enough to survive the Kuroshio current and that sails weren’t invented until about 5,000 years ago. They concluded that the ancient people most likely made dugout canoes out of tree trunks. So the researchers made their own tree trunk canoe using only the types of stone tools that the ancient people would have had.

The vessel wasn’t the only important part of the journey. In ancient times, every decision would have been important, including when and how the settlers traveled.

“We tested various seasons, starting points and paddling methods under both modern and prehistoric conditions,” researcher Yousuke Kaifu told the New York Times.

Courtesy of © Yousuke Kaifu/The University Museum, The University of Tokyo

Scientists used copies of ancient tools to chop down a tree and then used the wood to build a canoe.

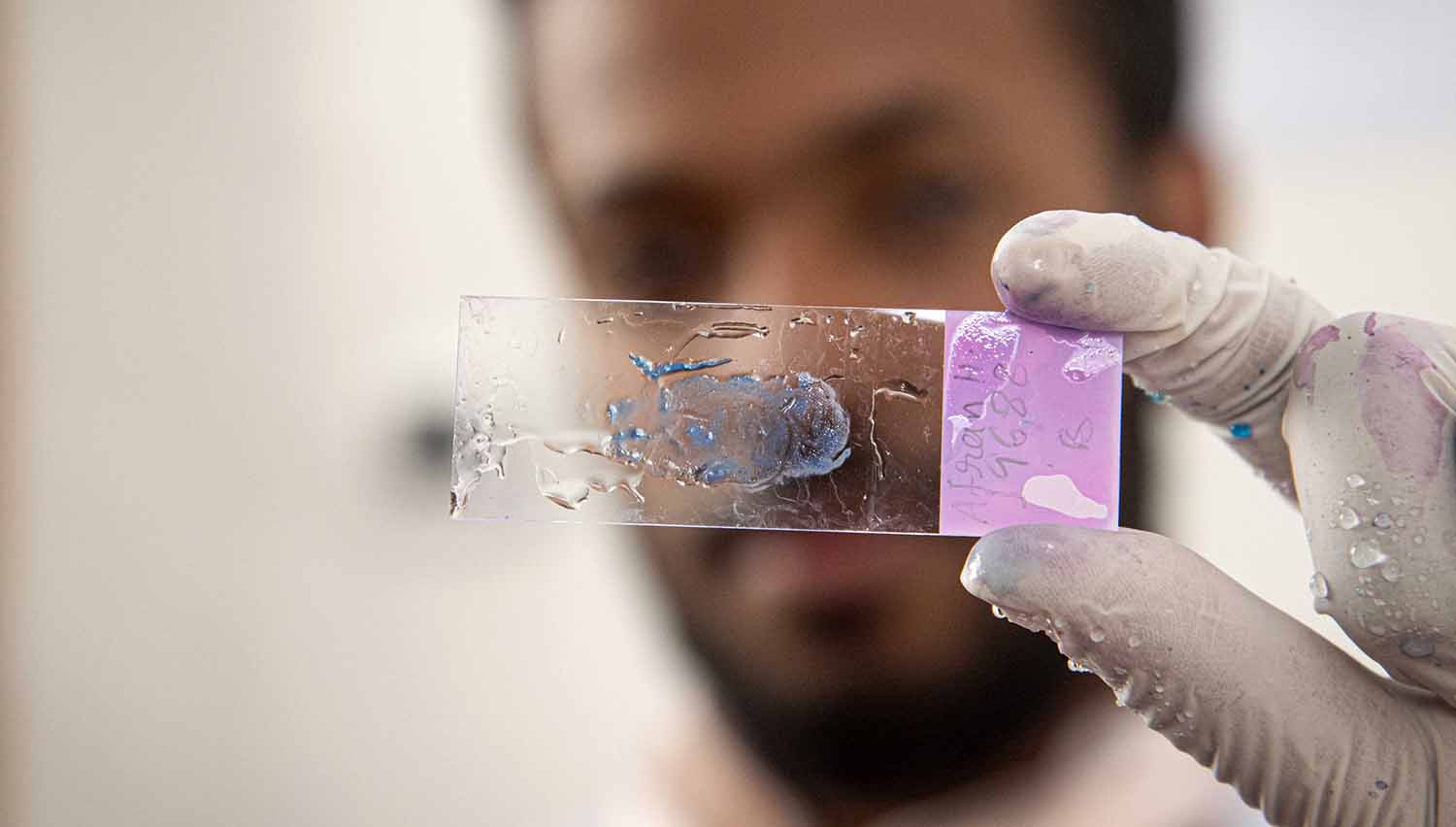

In July 2019, a crew of four men and one woman, all skilled canoe paddlers, set out from eastern Taiwan in the wooden canoe. The canoeists used only the Sun, stars, and tides to navigate to Yonaguni. (A modern boat traveled nearby to supply food and in case of emergency.) From hour 2 to hour 17 of the journey, the current became so rough that the crew had to make sure the wave water didn’t get into the canoe. After about 45 hours at sea, they arrived at Yonaguni. The researchers concluded that it wouldn’t have been possible for the ancient paddlers to travel back the way they came. The current would have been too rough.

The journey revealed that the people who landed at Yonaguni were skilled boat builders, paddlers, and navigators.

“This type of sea travel was possible only for experienced paddlers with advanced navigational skills,” the researchers later wrote.

Did You Know?

In 2023, Japan counted its islands again and found that it had over 7,000 more than previously thought. The new study brought the number of known Japanese islands to 14,125.

© kuremo—iStock Editorial/Getty Images

This photo shows just a few of the islands that make up Japan.

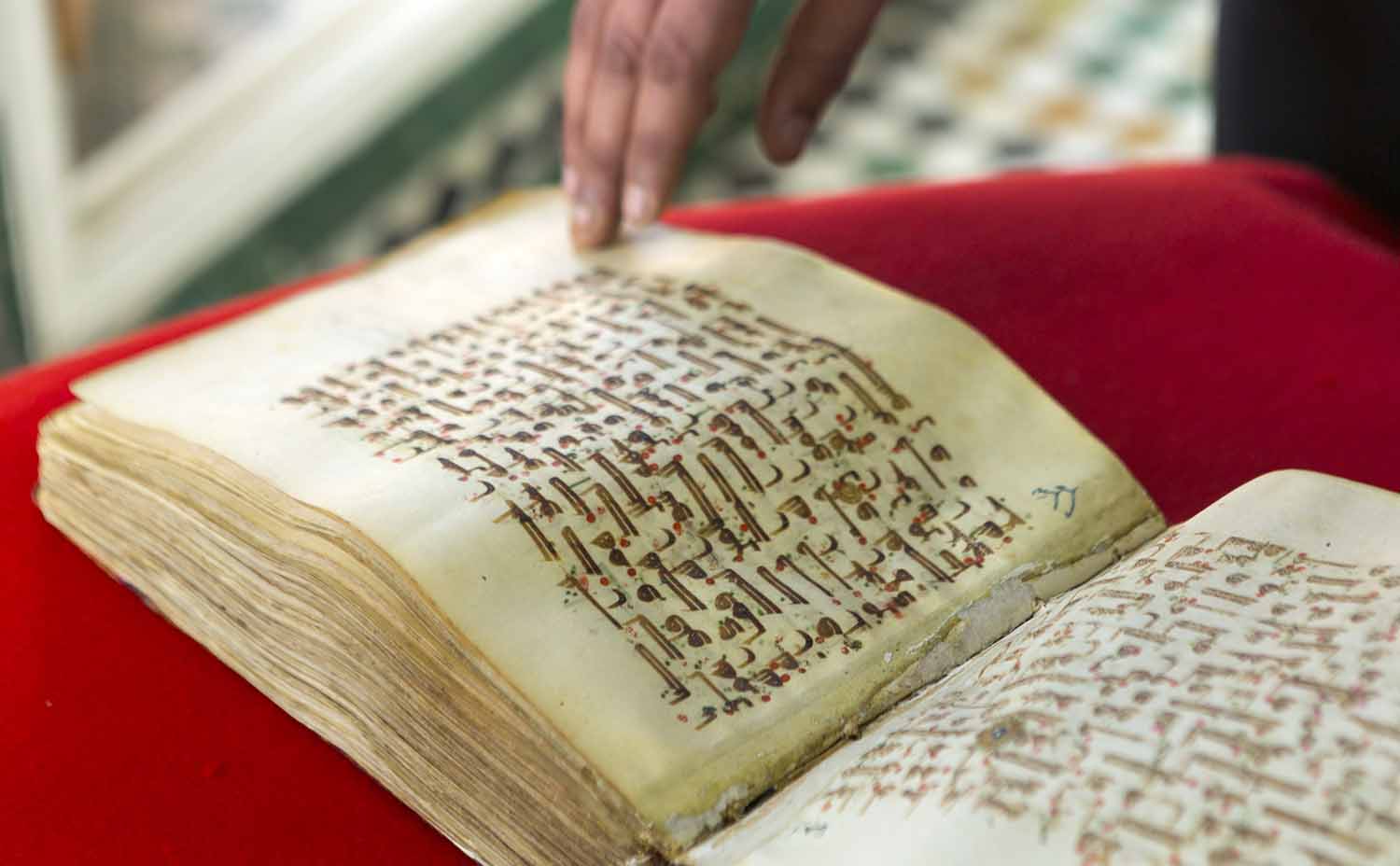

A Lost City?

© nudiblue—Moment Open/Getty Images

Scuba divers explore the area around Yonaguni Monument.

A rock structure in the water near the Japanese island of Yonaguni has mysterious origins. Discovered by a scuba diver in 1986, Yonaguni Monument is more than 165 feet (50 meters) long and 65 feet (20 meters) wide. There’s a strange symmetry to the rocks—meaning the angles at their corners are similar—as if it’s a structure that people built. The rocks also have markings that look as if humans made them.

Many experts believe that Yonaguni Monument was once a human-made pyramid, similar to the ancient pyramids of Egypt and South America. This would suggest that Yonaguni was the home of an ancient city that has been lost to history.

But other experts say the rocks’ arrangement is totally natural. They believe the rocks aren’t even symmetrical enough to have been shaped by people. Instead, they were shaped by underwater currents over thousands of years. And those markings? They could just be the result of wear and tear.

An Ancient but Modern Country

© Luciano Mortula-LGM/stock.adobe.com

First settled at least 30,000 years ago, Japan has since become one of the most advanced nations on Earth. Learn more about Japanese history, language, and culture at Britannica!

WORD OF THE DAY

replicate

verb

: to repeat or copy (something) exactly