The Story of the Six Triple Eight

In celebration of Women’s History Month, here’s the story of an all-female battalion that played a vital role in World War II.

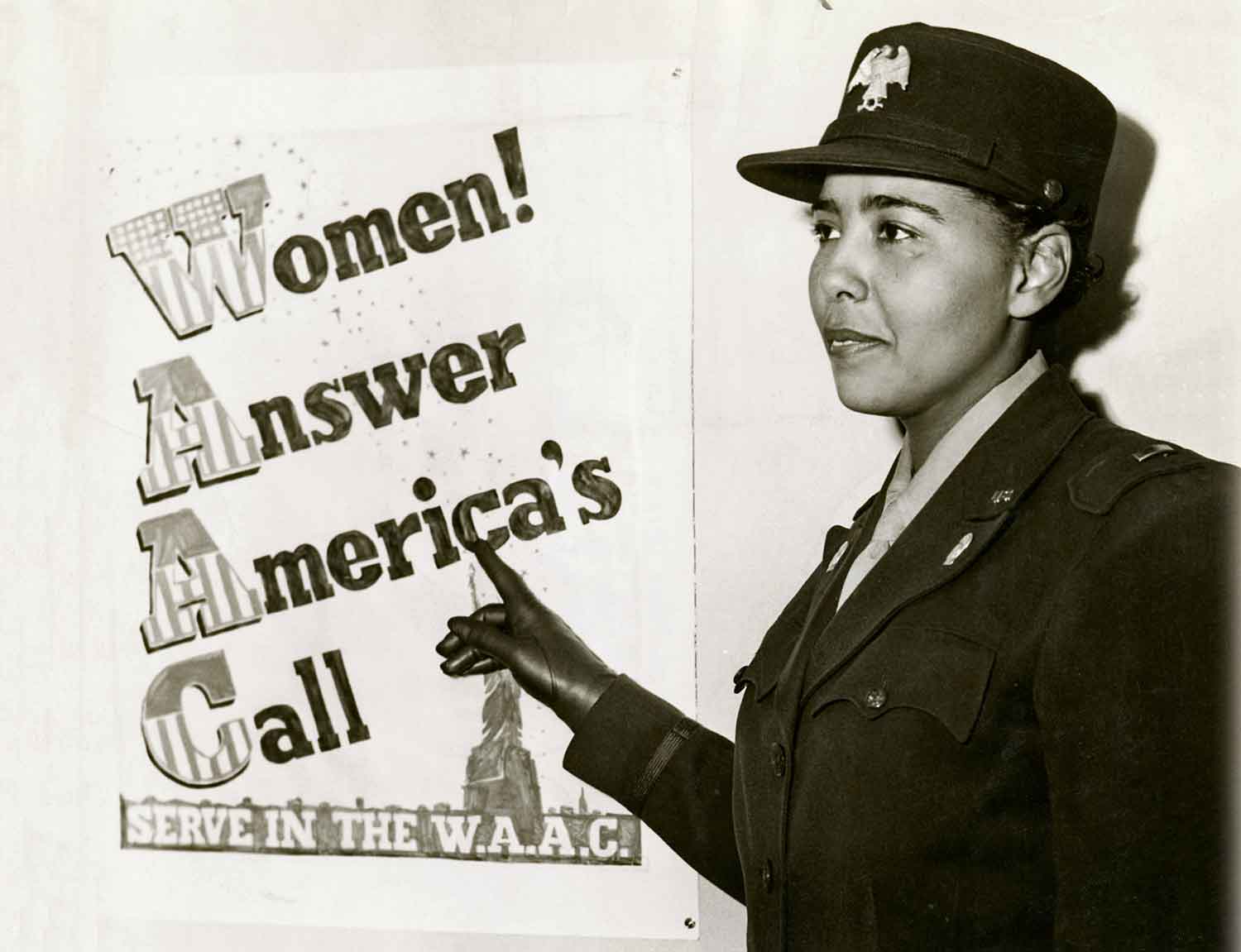

National Archives; U.S. Signal Corps; National Archives, Washington, D.C. (531249); Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library.

In February 1945, a group of American soldiers arrived in Birmingham, England, to begin serving in World War II. These soldiers were trailblazers. For one thing, they were all women at a time when the United States had only recently started to allow women to serve in the military. Also, the soldiers were Black. The 6888th Battalion (also known as the “Six Triple Eight”) overcame racism, sexism, and poor living conditions to play a vital role in the war.

At the time, women in the U.S. Army served in a noncombat branch that had been created in 1942. Originally called the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), it later became the Women’s Army Corps (WAC). About 6,500 Black soldiers were allowed in the WAC, but they had to sleep and eat separately from the white soldiers. At first, Black members of the WAC were told they would never be allowed to go overseas, where the war was taking place. But civil rights organizations pressured the government to change its policy. In late 1944, the 6888th was formed.

When they arrived in England in the winter of 1945, the members of the 6888th were sent to warehouses that were filled with letters and packages addressed to U.S. soldiers. Because of a shortage of postal workers, the mail had been piling up for months. The 6888th was told to sort the mail and see that each piece got to its recipient.

It was a monumental task, and not just because some letters and packages had vague addresses such as “John Smith, U.S. Army.” The warehouses were dark and lacked heat. Old packages of baked treats had been raided by rats. While off duty, the women faced racism and sexism from within the Army. Banned from living or eating with white soldiers, the members of the 6888th were required to use their own—poorly heated—facilities.

The Army didn’t show much confidence in the battalion’s commander, Major Charity Adams, who was a Black woman. At one point, a white general told her that he was going to send a white officer to tell her how to run the 6888th. She responded, “Over my dead body, sir.”

Major Adams and her battalion proved more than able to do their jobs. They set up a tracking system that allowed them to sort 65,000 pieces of mail per shift. The job was supposed to take six months. They finished in three months. The battalion was so successful that they were sent to France, where more warehouses of mail awaited them. Because of the 6888th, millions of soldiers received mail from their loved ones, an important part of keeping morale high during the war. But more than that, the success of the 6888th proved a point—that Black women were just as capable and hard working as white men.

The battalion’s accomplishments helped convince the U.S. government to make the armed forces fairer and more inclusive. In 1948, U.S. president Harry Truman signed legislation that ended racial segregation in the military. And, over time, additional laws were passed to allow female soldiers to take on new roles.